A comeback for value investing

Posted on: August 9, 2009

- In: Finance

- 2 Comments

The stock market has rallied 40 per cent in a flash; mid-cap stocks have kept pace with blue-chips and the action in small-cap stocks is reaching frenzied proportions, with many of them clustered at the upper circuit limit on any given trading day.

While speculative froth is undeniably building up in one segment of the market, there has been a rational element to how stock prices behaved in this unexpected rebound. Value investing, or buying stocks that trade far below their intrinsic value, has paid rich dividends in the bounce-back from the March trough.

And that’s not a flash in the pan. Our analysis shows that value investing has delivered good results for Indian investors over the long term as well. That contrasts with the popular notion that India is a “growth” market where investors shouldn’t mind paying a high price for alluring earnings prospects.

Value delivers

Consider the stock market surge from the recent low (8100 for Sensex). In the BSE-500 basket, the highest returns have been amassed by stocks with a PE multiple of less than 5. These stocks delivered an average 60 per cent gain between March 9 and now. Stocks with a modest PE below 10 averaged 53 per cent. Both classes of stocks easily outpaced the index return of 37 per cent.

Low PE stocks within each sector have also delivered better gains than their more expensive peers. Tata Motors has zoomed ahead of Maruti Suzuki (75 per cent versus 21), Reliance Communications has delivered thrice the returns of Bharti Airtel and Suzlon Energy has beaten NTPC hollow (65 per cent versus 6 per cent).

All three outperformers are clear instances where investors have bet on a deeply discounted price, brushing aside concerns on near term earnings or business uncertainties.

Further analysis shows that it is not just stock selection based on low PE that has worked. Investors who used other “value” filters — a high dividend yield or a low price-to-book value ratio — were rewarded equally well. Stocks with a high dividend yield (see table) have delivered a 55 per cent gain between March 9 and now, while those trading below their book value have gained 58 per cent.

Method in the madness

This cherry-picking of stocks ties in with the fact that the triggers for this market rebound came from instituional investors returning to Indian stocks. Since mid-March, there has been consistent FII buying and deployment of cash positions by domestic mutual funds and private insurers, even as retail investors cashed out. Institutional investors may have preferred undervalued stocks for two reasons. One, the ongoing slowdown has made it difficult for investors, even institutional ones, to make multi-year forecasts on revenues or earnings of companies. With projections subject to higher uncertainty, it appears safer to stick to stocks which discount only modest growth expectations.

Two, the steep market falls of last year and the 80-90 per cent erosion in some mid- and small-cap names has made investors pay greater attention to downside risk in recent times, leading to a “value” bias.

But is this partiality for low PE stocks a recent trend? Should investors go for less expensive stocks while building a long-term portfolio? While the answer to this question may have been very different during the bull market years from 2003 to 2007, recent evidence suggests that they should.

The market meltdown of 2008 has done much to restore the credentials of ‘value investing’ as a strategy suited to the Indian market. Though India is widely believed to be a growth market where institutional investors seek stocks for their heady growth prospects (and not for their bargain prices), today’s return numbers as of today, tell a different story. After two gut-wrenching market cycles, value stocks today sport a much better long-term track record than growth stocks, having delivered much better returns over 3, 5 and 10-year holding periods.

Compounded annual returns on the MSCI India Value Index (the key benchmark for value-style managers, Source: MSCI Barra) for a ten-year period at nearly 17 per cent, are at almost double the returns delivered by the MSCI India Growth Index (8 per cent).

A ten-year analysis shows that though growth stocks have made the most of the bull markets during their momentum years, value stocks did much better in containing falls during the inevitable reversal.

Given the tendency of the Indian market to swing (without warning) from a bull to a bear phase once every few years, it is the MSCI Value Index that has built up a better long-term track record than the Growth Index, till date.

For equity investors keen to build wealth over the long term, containing losses in a market fall may be as important as participation in upside during a bull phase. The message is, if you are looking at reasonable returns along with a less bumpy ride in the stock market, have a ‘value’ tilt to your portfolio.

Taking the lead

Another reason why investors may be better off owning under-valued stocks in market conditions such as this is that value stocks have usually led the initial leg of a market recovery from a bear phase.

As Indian markets commenced a new bull market after bottoming out in April 2003, the MSCI Value index climbed by 101 per cent in the eight months that followed, while the Growth index rose by just 77 per cent. Value stocks would also have delivered better returns after the May 2004 correction.

Value strategies also posted lower losses than growth-led ones during the vicious downturns in equities. The MSCI India Value index (decline of 42 per cent) fell much less than the Growth index (down 67 per cent) in the aftermath of the dotcom bubble.

This pattern was again repeated in the meltdown between January and November 2008, when the Growth Index plunged by 64 per cent while the Value Index got away with a 55 per cent decline (the US experience has been quite different; see accompanying article).

Add “value”

So what are the implications of the above trends for retail investors looking to rejig their portfolios?

With recent stock price gains driven mainly by re-rating of PE multiples (as the earnings picture remains quite bleak for many sectors), use the recent market rally to book profits in the more expensive stocks in your portfolio. That may also mean reducing exposure to the stiffly valued “defensive” stocks among FMCGs, power generation and pharmaceutical companies. Within sectors, switch to those that are available at less demanding valuations.

While adding cheaper stocks to your portfolio, beware of value ‘traps’— stocks that are trading at a low valuation, but could yet get cheaper as the company’s business or liquidity conditions deteriorate. Stocks of commodity companies (they appear cheap because of a high earnings base, which won’t be sustained), realty companies (who may post sharp profit falls) and the highly leveraged companies appear to be classic value traps in today’s context. If you find selecting value stocks a tricky proposition, take the mutual fund route. Most fund managers in the Indian context tend to be “growth oriented”. But value-focussed funds such as Templeton India Growth Fund, ICICI Pru Discovery Fund and UTI Dividend Yield Fund make a good addition to your portfolio.

Link Here..

Return on Assets (ROA)

Posted on: July 20, 2009

Return on Assets

Where asset turnover tells an investor the total sales for each $1 of assets, return on assets [or ROA for short] tells an investor how much profit a company generated for each $1 in assets. The return on assets figure is also a sure-fire way to gauge the asset intensity of a business. Companies such as telecommunication providers, car manufacturers, and railroads are very asset-intensive, meaning they require big, expensive machinery or equipment to generate a profit. Advertising agencies and software companies, on the other hand, are generally very asset-light (in the case of a software companies, once a program has been developed, employees simply copy it to a five-cent disk, throw an instruction manual in the box, and mail it out to stores).

Return on assets measures a company’s earnings in relation to all of the resources it had at its disposal [the shareholders’ capital plus short and long-term borrowed funds]. Thus, it is the most stringent and excessive test of return to shareholders. If a company has no debt, it the return on assets and return on equity figures will be the same.

There are two acceptable ways to calculate return on assets.

Option 1:

Net Profit Margin x Asset Turnover

Option 2:

Net income

———–(divided by) ———–

Average Assets for the Period

The lower the profit per dollar of assets, the more asset-intensive a business is. The higher the profit per dollar of assets, the less asset-intensive a business is. All things being equal, the more asset-intensive a business, the more money must be reinvested into it to continue generating earnings. This is a bad thing. If a company has a ROA of 20%, it means that the company earned $0.20 for each $1 in assets. As a general rule, anything below 5% is very asset-heavy [manufacturing, railroads], anything above 20% is asset-light [advertising firms, software companies].

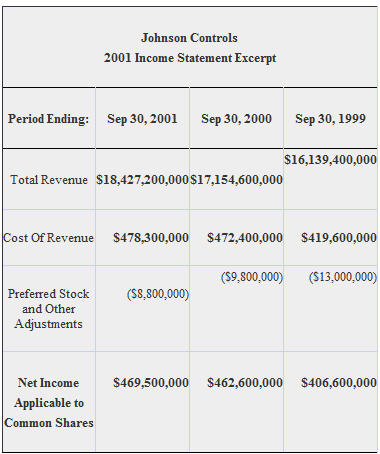

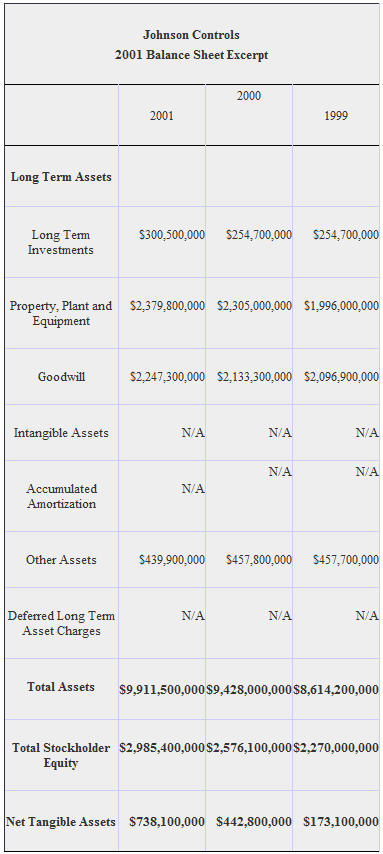

The first option requires that we calculate net profit margin and asset turnover. In most of your analyses, you will have already calculated these figures by the time you get around to return on assets. For illustrative purposes, we’ll go through the entire process using Johnson Controls as our sample business.

Our first step is to calculate the net profit margin. We divide $469,500,000 [the net income] by the total revenue of $18,427,200,000. We come up with 0.025 (or 2.5%).

We now need to calculate asset turnover. We average the $9,911,500,000 total assets from 2001 and $9,428,000,000 total assets from 2000 together and come up with $9,669,750,000 average assets for the one-year period we are studying. Divide the total revenue of $18,427,200,000 by the average assets of $9,660,750,000. The answer, 1.90, is the total number of asset turns. We now have both of the components of the equation to calculate return on assets:

.025 [net profit margin] x 1.90[asset turn] = 0.0475, or 4.75% return on assets

The second option for calculating ROA is much shorter. Simply take the net income of $469,500,000 divided by the average assets for the period of $9,660,750,000. You should come out with 0.04859, or 4.85%. [Note: You may wonder why the ROA is different depending on which of the two equations you used. The first, longer option came out to 4.75%, while the second was 4.85%. The difference is due to the imprecision of our calculation; we truncated the decimal places. For example, we came up with asset turns of 1.90 when in reality, the asset turns were 1.905654231. If you opt to use the first example, it is good practice to carry out the decimal as far as possible.

Is a 4.75% ROA good for Johnson Controls? A little research on MSN Money Central shows that the average ROA for Johnson’s industry is 1.5%. It appears Johnson’s management is doing a much better job than the competitors. This should be welcome news to investors.

Read More..

You Need to Know ROA and ROE

Posted on: July 20, 2009

Return on Assets (ROA) and Return on Equity (ROE) are superficially similar, but their differences lead to useful business insight. In this easy-to-digest and simplified primer we aim to demystify the concept of debt leverage, the fundamental driver of differences between ROA and ROE. A solid grasp of this basic concept sets the stage for successful further study of the details, and can help make you a better investor.

While computing common measures of business success is often an adventure, it’s usually not an overwhelming barrier to understanding public companies. You find the raw numbers on the financial statements, plug them into the formulas, and crank out the results. What is especially difficult for most of us, though, is figuring out which formulas we should rely on in a given business scenario and exactly what the results tell us. (You can find out other user-friendly ways to evaluate businesses in our popular online seminar, Choosing Stocks With The Motley Fool, starting September 13th.)

Our case in point here highlights two similar measures: Return on Equity (ROE) and Return on Assets (ROA). On the surface, both are straightforward ratios of a company’s earnings to the amount of upfront investment that went into generating these earnings. This is how ROE and ROA are the same. The tricky — and interesting — part is digging deeper and asking how these two are different.

To really grasp the difference between ROE and ROA, you have to become very comfortable with one basic idea — debt leverage. Personally, I grappled for a long time with the concept of leverage and, consequently, with the difference between ROE and ROA. The breakthrough took place when I began to think more carefully about something simple — the fundamental accounting formula.

Back to basics

The fundamental accounting formula looks like this:

Owner’s Equity = Assets – Liabilities

If this relationship isn’t already second nature to you, perhaps the most easily understood example is home ownership. Let’s say that my house is worth $100,000 on the open market and that my outstanding mortgage loan balance is $75,000. Then:

My Equity = Home Value – Loan Balance

Or

$25,000 = $100,000 – $75,000

Now, starting with this fundamental accounting relationship, let’s do the simplest of algebraic manipulations to get:

Assets = Owner’s Equity + Liabilities

Continuing our home ownership example, this translates into:

Home Value = My Equity + Loan Balance

Or

$100,000 = $25,000 + $75,000

Take a good look at this last pair of equations. It may look a little funny at first glance, but if you stare at them long enough you’ll see a familiar concept. In everyday language, we often hear:

My House = My equity + The bank’s loan

This explanation glosses over a subtle but important detail that we’ll look at later. For now, however, it is all that we need to tackle the root of all differences between ROA and ROE.

Tackling debt leverage

With the basics in hand, let’s leave home mortgages behind and delve into a corporate example. Suppose ScootCo (Ticker: OUCH) is a long-time, low-growth manufacturer of slick two-wheel scooters for kids. Its major assets are the plant where its scooters are assembled and its brand name. These two assets combined could be sold for (have a market value of) $100,000. Finally, let’s assume OUCH has no long-term debt outstanding.

Simplistically then, we can sum up its financial situation with our rearranged accounting formula as follows:

Assets = Equity + Liabilities

Or

$100,000 = $100,000 + 0

In other words, if there is no debt, then owner’s equity and the total value of corporate assets are one and the same number. From this observation, it follows that Return on Equity and Return on Assets must also be the same number (since the Return doesn’t change and Equity and Assets are equal). If we ignore the vagaries of working capital for the moment, then, we see that the special case of “no debt” implies that ROE = ROA.

So, let’s put some debt into our example to make things interesting. Suppose the demand for kids’ scooters suddenly explodes, presenting OUCH with a golden opportunity to grow its business. Seizing the moment, the scooter execs decide to increase production capacity by 50% and head to their friendly banker for a loan of $50,000 to expand the plant. And the moment this $50,000 check hits their hot, little, scooter-lovin’ hands, we can update our rearranged accounting formula as follows:

Assets = Equity + Liabilities

Or

$150,000 = $100,000 + $50,000

Compare this formula to the one above it and, again, stare carefully; the comparison leads directly to the key idea behind debt leverage:

Taking on debt increases assets and liabilities by the same amount, but has no impact on owner’s equity

With this example in hand, the derivation of the term “leverage” should be clear. Debt adds to the assets owned by a business without any further investment required by the owners. Sounds great, eh? But is it?

Tying it all together

Continuing with our corporate example, let’s use both ROE and ROA to measure the success of OUCH one year after the $50,000 expansion. We’ll assume the increased production boosts OUCH’s profits by 50%. To keep things as simple as possible, we’ll ignore any tax benefits arising from loan interest payments.

Prior to the expansion

No debt

Assume OUCH is producing a reliable annual profit of $10,000

Assets = Equity = $100,000

ROE = ROA = $10,000 / $100,000 = 10%

Post-expansion

$50,000 debt (liability)

Annual interest payment of $3,000 (6% of $50,000)

Scooter profit = $15,000 (50% boost to $10,000)

Net profit = $15,000 – $3,000 = $12,000

Assets = $150,000

Equity = $100,000

ROA = $12,000/$150,000 = 8%

ROE = $12,000/$100,000 = 12%

What’s it all mean? Well according to ROA, our scooter execs blundered in expanding the plant, shaving 2% from their return on investment, from 10% down to 8% (even though profits increased 20%). According to ROE, however, they did the right thing, improving return by 2%, to 12%. So, which is the right interpretation?

Like all answers worth a darn, this one is: “it depends.” Think of ROA as the fundamental business engine. ROE is what happens when you leverage this fundamental business engine by taking on debt. If the engine is sound (produces a positive return on assets), taking on debt to expand the engine will improve shareholders’ return. As we saw in this example, the debt doesn’t even have to improve the fundamental business engine (ROA) to improve shareholders’ return (ROE). It just can’t degrade the engine too much.

If the engine is not sound, however, taking on debt will exacerbate shareholder losses, since the company will have to continue making debt payments on assets, even as ROA collapses. This vicious cycle can strike even when the ROA engine collapse is only temporary, as is often the case during broad economic slowdowns.

So the answer is: Look at both. If ROA is sound and debt payments are under control, improving ROE is a sign of successful management. On the other hand, if ROA is declining, or the company does not appear financially sound enough to withstand troubled times, improving ROE could be just a temporary illusion — a harbinger of serious trouble

Read More..

The Mighty SIKHS

Posted on: July 20, 2009

Sikhs are very brave. (Maj. Gen. Mukesh Khan Pakistan Army, author of book “Crisis of Leadership”)

“The major reason for our defeat are Sikhs. We are simply unable to do anything before them despite our best efforts. They are very daring people and are fond of martyrdom. They fight courageously and are capable of defeating an army much bigger than them.”

On 3rd December 1971 we fiercely and vigorously attacked the Indian army with infantry brigade near Hussainiwala border. This brigade included Pakistan army’s Punjab regiment together with the Baloch regiment. Within minutes we pushed the Indian army quite far back. Their defense posts fell under our control. The Indian army was retreating back very fast and the Pakistani army was going forward with great speed.

Our army reached near Kausre-Hind post (Kasure). There was small segment of Indian army appointed to defend that post and their soldiers belonged to the Sikh Regiment. A few number of the Sikh Regiment stopped our way forward like an iron wall. They greeted us with the ovation (Slogan) of ‘Bolé-so-Nihal’ and attacked us like bloodthirsty, hungry lions and hawks. All these soldiers were Sikhs. There was even a dreadful hand-to-hand battle. The sky filled with roars of ‘Yaa Ali and Sat Sri Akal’. Even in this hand-to-hand fighting the Sikhs fought so bravely that all our desires, aspirations and dreams were shattered.

In this war Lt. Col. Gulab Hussain was killed. With him Maj. Mohammed Zaeef and Capt. Arif Alim also died. It was difficult to count the number of soldiers who got killed. We were astonished to see the courage of those, handful of Sikh soldiers. When we seized the possession of the three-story defense post of concrete, the Sikh soldiers went onto the roof and kept on persistently opposing us. The whole night they kept on showering fires on us and continued shouting the loud ovation of ‘Sat Sri Akal’. These Sikh soldiers kept on the encounter till next day. Next day the Pakistani tanks surrounded this post and bombed it with guns. Those, handful of Sikhs got martyred in this encounter while resisting us, but other Sikh soldiers then destroyed our tanks with the help of their artillery. Fighting with great bravery they kept on marching forward and thus our army lost its foothold.

Alas! A handful of Sikhs converted our great victory into big defeat and shattered our confidence and courage. The same thing happened with us in Dhaka, Bangladesh. In the battle of Jassur, the Singhs opposed the Pakistan army so fiercely that our backbone and our foothold were lost. This became the main important reason of our defeat; and Sikhs’ strength, safety and honour of the country, became the sole cause of their victory.

Daily SIP ?

Posted on: June 22, 2009

How do you avoid or minimise the effects of an extremely volatile stock market? Given the choice between the asset classes, and the yo-yoing of almost every fund, do you dare to invest in it at all? What if there was a middle path?

The Systematic Investment Plan is ideal for investors who have a regular flow of money (such as employees). A simple instruction to the fund house and the bank will help them invest regularly at a given time and stay away from the volatility of the stock market.

When you invest a fixed amount, such as Rs 5,000 a month, you buy fewer units when the share prices are high and more units when the share prices are low.

The reinvention of the Systematic Investment Plan (SIP) has been a boon for investors with a low-risk appetite. Rupee cost averaging and compounding are added advantages. But what exactly is a Daily SIP? And how does it benefit you, the customer?

So what is Daily SIP?

Simply, a Daily SIP collects a small sum from an individual on a daily basis and invests it in the market. It operates like any mutual fund, where the disbursement and handling of the money is the fund manager’s prerogative.

Rupee cost averaging occurs when the market goes down, and more units of the scheme can be purchased because of a lower net asset value. However, most companies have SIP schemes that allow you to invest on different dates of the month.

Daily SIPs are expected to minimise risk and generate greater risk-adjusted returns while increasing participation.

Daily SIPs: Advantages

Affordability, volatility and convenience are the most obvious advantages of investing in a Daily SIP.

- With a Daily SIP, your investment is staggered. Instead of a lump-sum amount, you invest a pre-specified amount in a scheme at pre-specified intervals at the then prevailing NAV (Net Asset Value).

- Consistent monetary contributions average out the crests and troughs of any market, in the long term.

- It also captures the daily levels of market volatility. In case of a monthly SIP, you still can lose out if the markets are up on the chosen day of the month. The daily SIP, however, eliminates this flaw and lets you benefit out of equity market volatility.

- If you’re looking at a lump-sum investment, then going in for a daily SIP would allow you to take advantage of the market volatility, by splitting the lump sum amount in to daily instalments over a relatively short time frame.

- The Daily SIP is ideal for small time savers, since the threshold investment level is low.

- Once you start with a Daily SIP, you invest at the appointed time and that makes you a disciplined investor.

- With Daily SIPs, you capitalise on the periodic dips in the market and accumulate a greater number of units at lower levels — and over time, reduce your average unit cost.

- You avoid the lure and trap of trying to predict the market.

A word of caution

Usually, a fund charges 2.25 per cent of invested amount as the ‘entry load’. However, in some cases this amount may get reduced. You should also keep in mind the contribution after taking into account the cash flows available.

Check if there are any incremental transaction charges attached to each investment. Especially in the case of auto-debit, there may be a fee for every transaction.

You need to remain invested in a Daily SIP for at least 3 years to reap the benefits, and monitoring this on a daily basis can be annoying.

If you should fail to pay the SIP amount on any particular working day, your investment will not default but your return will be adjusted against the failure of payment for that day.

Stocks Analysis Tips

Posted on: June 19, 2009

- In: Investments

- 1 Comment

1. Low Debt-Equity ratio stocks If the ratio is lower than one, it means the company has a lesser debt burden. The positives of such companies are that they need only a lesser amount to be kept aside to pay the interests that arise out of loans. The fluctuations in interest rates during high inflationary situations may have little impact on the financials of such companies. So companies that have zero debt should be targeted with a medium to long-term perspective.

2.Stocks trading below their book values he book value of a company is the cost of an asset minus accumulated depreciation. In other words it is the total value of the company’s assets that shareholders would theoretically receive if a company is liquidated. So, if a stock is trading below its book value, then it is underpriced, and should therefore be seen as an opportunity to make an investment in that stock.

3. Following the averaging pattern of investment Investors should follow the averaging pattern of investment when the markets are volatile and not giving any trends. This will put the investors in a better position. The investor has to enter the market at three or four different times which will help the investor to reduce the per share price of his holdings.

10 Fascinating Angels and

Posted on: June 12, 2009

10 Fascinating Angels and Demons

Posted using ShareThis

Top 15 Greatest Epic History

Posted on: June 12, 2009

Top 15 Greatest Epic History Movies

Posted using ShareThis

which is more aggressive investment instrument?

The ELSS fund is a 3 year scheme. Most funds are open ended and you can stay invested after 3 years. Each investment into the elss fund needs to be kept for 3 years. A ULIP has a cumulative lock in of 3 years. (all 3 year premiums can be withdrawn once the lock in expires. Both provide tax free returns. The ELSS fund is completely invested in equities, in the case of the ULIP Switches can be made between funds. Intra fund switches are not taxable in the case of the ULIPs. The ULIPs provide you with life cover while the MF does not. ULIPs are higher cost in the short term (less than 6 years); in the long term, some ULIPs can be cheaper than MFs due to the lower fund management charges. A ULIP should only be considered if the investment horizon is greater than 6 years. Weigh the pros and cons before investing.

Comments